Legendary ad man and agency founder David Ogilvy once noted, “If each of us hires people who are smaller than we are, we shall become a company of dwarfs. But if each of us hires people who are bigger than we are, we shall become a company of giants.”

Why should this attitude stop at hiring? As leaders, our role is to continuously develop our people, teaching them new skills and encouraging them to take on new and greater opportunities. Development, though, can feel like a minefield. How do you teach new skills without micromanaging? How can you provide feedback without seeming critical?

"If you want to create a culture of learning, there’s no substitute for holding a regular meeting to discuss work and provide feedback."

In my role as managing director of NOBL UK (a global change agency that helps world-class organizations design their cultures), I’ve found that one of the most critical tools for building better relationships with direct reports is the easiest to overlook: the humble one-on-one. This misunderstood meeting is all too often thought of as a pure status update, leading to a recitation of to-dos, or it’s treated like a social occasion, and issues of substance go undiscussed.

It’s not surprising, then, that one-on-ones are cancelled or indefinitely rescheduled when “more important” meetings appear on the calendar. But if you want to create a culture of learning, there’s no substitute for holding a regular (at least monthly; every other week is better) meeting to discuss work and provide feedback.

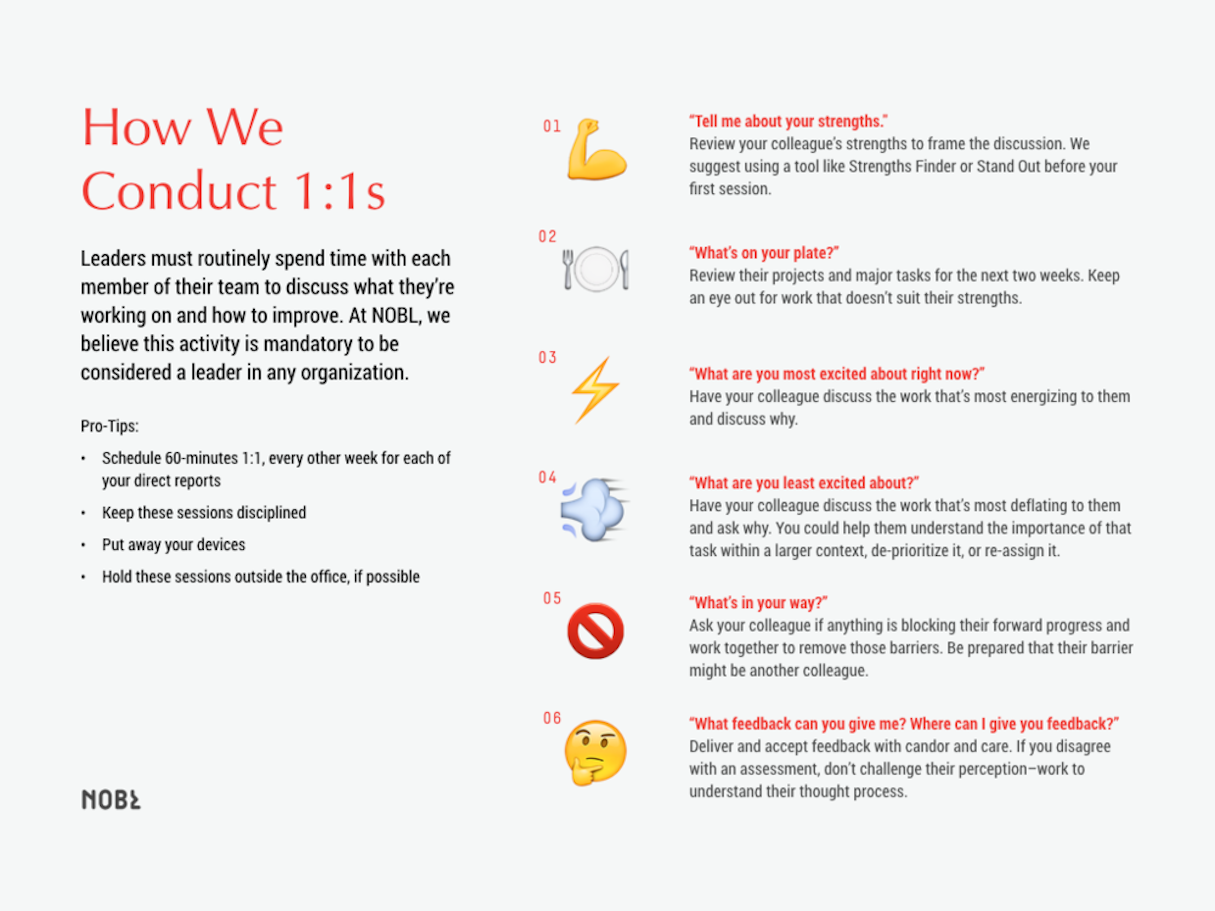

When I work with leaders who are seeking to improve their one-on-ones, we break them down into three main components:

- Strengths and career development

- The work ahead

- Feedback

In this article, we’ll discuss simple tools and prompts that you can use to guide discussions with your direct reports, which will ultimately create a culture of continuous learning and employee engagement at your organization.

1. Strengths and development

We start every one-on-one with a simple question: what are your strengths? We want every employee to feel like they have an opportunity to do their best work, as well as continue to learn and grow within the organization. Invite your direct report to reflect on their experiences at work: what makes them feel energized? What do their peers miss when they’re not in the office?

Of course, not everyone has a clear understanding of what their strengths are, or how they want to develop—especially if they’re a more junior employee. To set a baseline, try any of the following tools.

Digital assessment

There’s no shortage of digital tools, such as Clifton Strengths or Stand Out, to help individuals evaluate their strengths (in fact, your organization may already have a preferred tool, so check with your HR team first). A word of caution: we’d recommend looking for tools that focus on strengths as opposed to personality, which will keep the focus on “how people behave” as opposed to “who they are.”

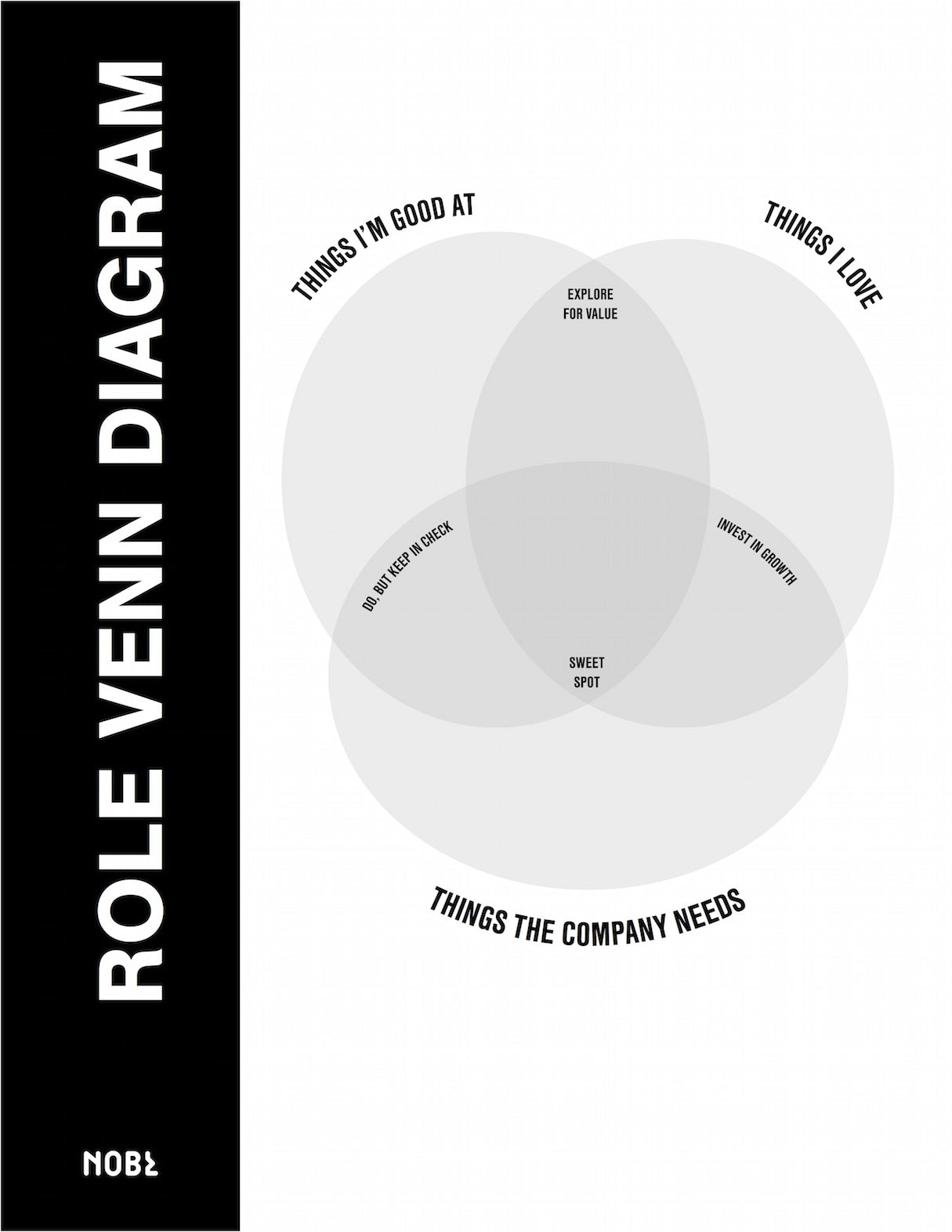

The Ikagai diagram

Inspired by ikagai, the Japanese word for “reason for being,” we’ve modified a Venn diagram of three overlapping circles:

- What you like doing

- What you’re good at

- What the business needs

Work with your direct report to think through their skills and map them to the appropriate part of the diagram. In the long-term, of course, the goal is for skills to live at the confluence of all three circles, but they may need help getting there.

For skills that the employee loves and the business needs, but isn’t necessarily good at: develop a training plan. Discuss opportunities to improve these skills—on-the-job training, formal coursework—milestones that will indicate mastery, and add timelines for improvement.

For skills the employee is good and at the business needs, but doesn’t particularly love: look for opportunity to delegate or automate these tasks as much as possible, or have them train someone else who does enjoy that skill. It’s understood, of course, that every job will have elements that are less than fun!

For skills that the employee loves doing and is good at, but that the business doesn’t need: look for ways to capitalize on it. Is there an overlooked business opportunity, or another segment of the business that would benefit from these strengths?

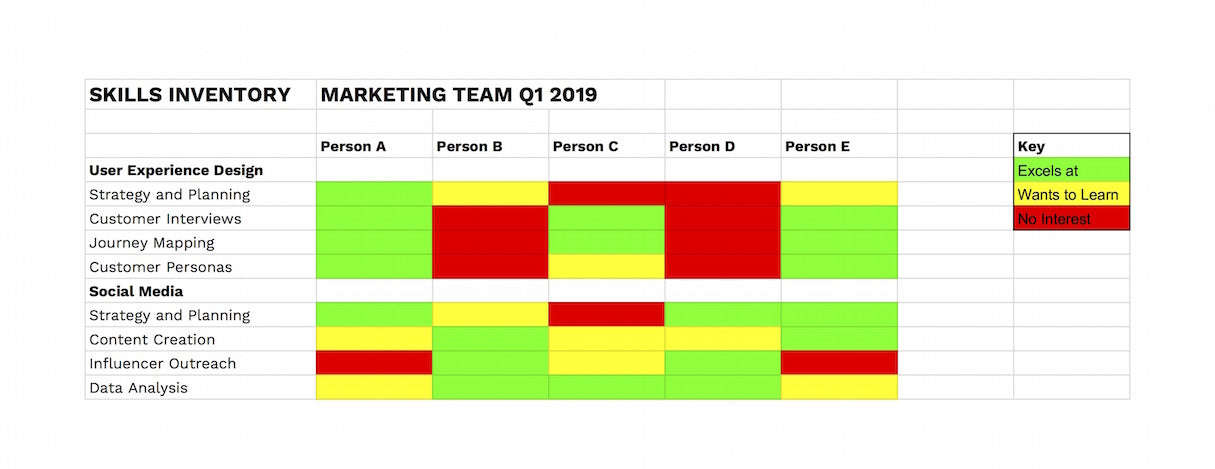

Skills inventory

A skills inventory is useful not just for tracking individual development—it also provides a snapshot of where the team as a whole excels or needs to improve.

- First, identify all the skills or tasks that your team requires, such as “UX Design” or “Prospecting Calls.” It’s easiest to compile this information in spreadsheet.

- Next, ask each individual to review the skills and identify:

- Which skills they excel at

- Which skills they would like to learn

- Which skills they have no interest in working on whatsoever

Once you have an understanding of how your direct report wants to grow, you can use this as a lens for assessing what they’re working on—are the tasks best suited to their skill set? And as new projects come up, you can refer to these tools to identify opportunities for people to learn the skills they’re interested in.

If your assessment of your direct report’s skills don’t align with their assessment, the one-on-one provides an excellent opportunity for you to provide feedback and set up milestones, so that both of you can agree what progress looks like—but we’ll get to that in a moment.

You might also like: 10 Essential Front-End Developer Skills to Help You Move Faster in Your Career.

2. The work ahead: Adopting the coach approach

Now that you’ve established and reviewed the direct report’s strengths, it’s time to review the work ahead. Don’t think of this as a status update, but rather, as an opportunity to discuss how they’re approaching the work. Start with three simple questions:

- What’s on your plate?

- What are you excited about?

- What are you least excited about?

Again, evaluate the work based on their strengths and interests—are there new projects that will help them level up a skill? How have they been developing or practicing the skills they’ve indicated they want to learn? And are there any tasks that should be removed from their plate because they’re just not great at it?

Solving problems

Once you’ve sorted through the work to be done, ask your report one simple question: “What’s in your way?”

Then, stop. Don’t try to fix it. At least, not yet.

When high-performing leaders a presented with a problem, their immediate response is to solve it—after all, that’s what got them to their current position. But solving your team’s problems all the time means that they never develop their own problem-solving capabilities and makes you a bottleneck for all decisions.

"Solving your team’s problems all the time means that they never develop their own problem-solving capabilities and makes you a bottleneck for all decisions."

Instead, your role as leader is to serve as coach, helping them hone the expertise and skills they need to address the problem. At first, this will feel scary for both the leader and the employee—what if they get it wrong? The key is to set boundaries and analyze trade-offs so that you both feel comfortable with the level of risk.

So the next time a member of your team approaches you with a problem, instead of leaping to a solution, slow down the conversation by asking questions like:

- What potential solutions have they considered?

- What are the potential consequences of each solution, and should it be implemented?

- Are there any roadblocks to implementing a given solution?

- Based on this analysis, what do they recommend?

Working through the problem together will accomplish two goals: first, your employee will learn how you approach a problem, and the calculations and trade-offs that you’re willing to make to address an issue. Second, it will give you peace of mind, in that you’ll have vetted the solution before it moves forward.

Next steps in their work

The last step is to help your report break down the work ahead. You can do so by asking the following questions:

- What’s the very next step that they must take?

- How will they know if they’re making progress towards their goal?

- What should they do if progress stalls or another problem comes up?

This process can take some getting used to, so if you’re new to it, practice with a colleague first. Ask them to describe a dilemma that they’re having, and then challenge yourself to only ask questions for an entire minute—you might be surprised how long that minute feels!

For inspiration, check out the Question Game from Whose Line Is It Anyway.

You might also like: Team Management Skills 101: Level-Up as an Agency Leader.

3. A better way to give feedback

The last portion of your one-on-one should be dedicated to giving (and receiving!) feedback. When people hear the term “feedback,” they often associate it with criticism. But not only can feedback be positive, research indicates that the ratio of positive to negative feedback should be as high as 6:1! After all, it’s easier for people to keep doing the right thing rather than changing what they’ve been doing wrong. And for those of you thinking that people just need to toughen up—research suggests that negative feedback triggers the “fight or flight” impulse, which actually impairs learning.

To make the most of your feedback session, consider the following.

Take a moment to self-reflect

Are you in the appropriate mindset to give feedback? For instance, maybe you’re still dealing with the after-effects of a rough morning and are looking to displace some of your annoyance. Or maybe your desire to provide feedback is because you want to show how much smarter you are, rather than from a place of genuine desire to help others improve.

If you find your motivations for giving feedback are questionable, pause. Make a note of the feedback, and return to it once you’re in a more neutral emotional state.

Praise in public, criticize in public

Evaluate the nature of your feedback. If it’s positive, you may want to share feedback in public, as it will serve as a model for others to follow. If it’s negative feedback, though, deliver it in a private setting. Criticizing someone in a public forum will not only embarrass them, it will also reduce your team’s appetite for taking risks, as they won’t want to be castigated in public.

Ask for permission to give feedback

A one-one-one has a built-in section for feedback, but it’s still important to get in the habit of asking. Asking for permission gives them control of the situation, and time to reflect on whether or not they’re in a good space to receive feedback.

Note that it’s okay for them to say no—but they then do have to come back with a more acceptable time, rather than push it off indefinitely.

Make it timely

No one likes to have difficult conversations, so it’s easier to, well, not have them. But if you don’t address a mistake as soon as possible, it will be repeated—and when you do finally provide feedback, they’ll wonder why you didn’t address it sooner.

That’s why I strongly encourage leaders to hold to regular one-on-ones. It makes feedback a commonplace event, as opposed to a catastrophe. It’s also why you shouldn’t ask your direct report “Do we really need to have this one-one-one?” Show that you value their time and are willing to commit to their development.

Be specific

Focus in on one or two areas of improvement, and how it affected you. Research indicates that feedback is in fact far more subjective and biased than we realize—the idiosyncratic rater effect. So instead of saying “You didn’t make your point during the presentation,” for instance, try “I didn’t see the connection between the points during the presentation.”

Don’t give them a shit sandwich

In an effort to make criticism more palatable and soften the blow, most people will give feedback in the form of a shit sandwich: a compliment, followed by the criticism you actually wanted to give, followed by a compliment.

We discourage this method, as people quickly learn to distrust positive compliments and wait to hear the “actual” feedback. Instead, try the “star and a wish” method: find a behavior that they’re performing well in one area of their work, and ask them to apply that same behavior to another way, or to another area of the business.

Ask them for feedback

Model the behavior you want to see to encourage a culture of learning, and find out if they have feedback for you. This will not only help make everyone feel like they can improve the workplace, but will also give them good training for when they become a manager one day.

You might also like: Giving Feedback: What We’ve Learned About Building Strong Design and Development Teams.

Trust takes time

Building a culture of trust and candor is challenging, and it doesn’t happen overnight. But establishing and sticking to a rhythm of regular one-on-ones will foster the relationships you need to take your team to the next level.

Need a little help remembering all this? We’ve prepared a cheat sheet (see above)—feel free to use it during your next session.