No longer able to rely on advertising, publishers are diversifying and increasingly turning to ecommerce as a revenue model.

1. The New York Times

The New York Times has been offering readers “all the news that’s fit to print” since 1851. Today, the Times is succeeding where other publishers have fallen on hard times: $1.78 billion annual revenue in 2020, online subscription growth, international expansion, and new forms of storytelling—namely, its podcast, The Daily.

At the end of Q4 2020, The New York Times reported that its digital revenue overtook print for the first time, while its digital subscription revenue—long its fastest-growing revenue stream—has become its largest. The paper now has 7.5 million subscriptions, of which 6.7 million are digital-only.

“The last 10 years were about proving our strategy of journalism worth paying for; the next 10 will be about scaling that idea,” said the Times’ president and chief executive officer, Meredith Kopit Levien, in a press release. “With a billion people reading digital news, and an expected 100 million willing to pay for it in English, it’s not hard to imagine that, over time, The Times’s subscriber base could be substantially larger than where we are today.”

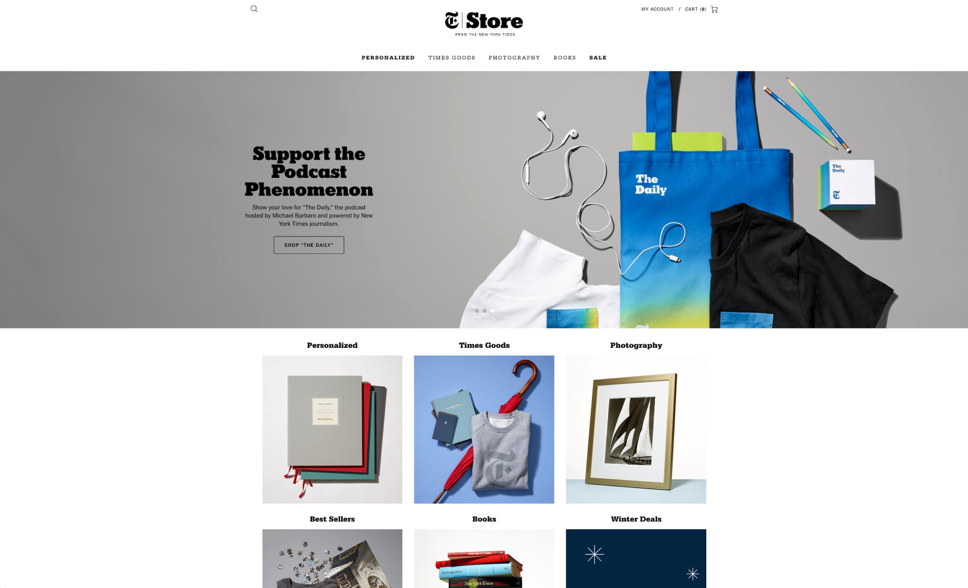

Always forward-thinking, the NYT’s direct-to-consumer offering gives its expanding reader base an additional touchpoint for connecting with its journalism. In its online store, the company sells branded goods, archival photography, books, and personalized front page reprints.

However, what’s truly innovative is how the NYT has taken its extensive library of print and digital content and monetized them both by offering readers custom products.

For instance, it offers made-to-order custom publications, such as its best-selling Ultimate Birthday Book. More recent lines, including its cooking collection, have resulted from collaborations with newsroom editors and reflect the values and sensibilities of the communities they’re designed for.

“Retail is a game of trade-offs, so it’s important to build consensus around why your publication needs a store in the first place,” says Robyn Metzger, the director of the Times’ online store. “Work with stakeholders to develop a set of principles from there, and then make it your job to stick to those principles.”

Learn more: Direct to Consumer vs Wholesale: Customer Experience Over Competition

2. BuzzFeed

When you’re the place the internet turns to for popular culture—think trends, lists, quizzes, memes, GIFs, entertainment news—it makes sense that you would venture into selling merch.

That’s what BuzzFeed did in 2016.

The company’s flagship product was the Tasty One Top, an induction cooktop with app integration made by Cuisinart. It grew out of BuzzFeed’s Tasty, the world’s largest social food network. (At the risk of getting meta, The New York Times covered that story under the headline, “How BuzzFeed’s Tasty Conquered Online Food.”)

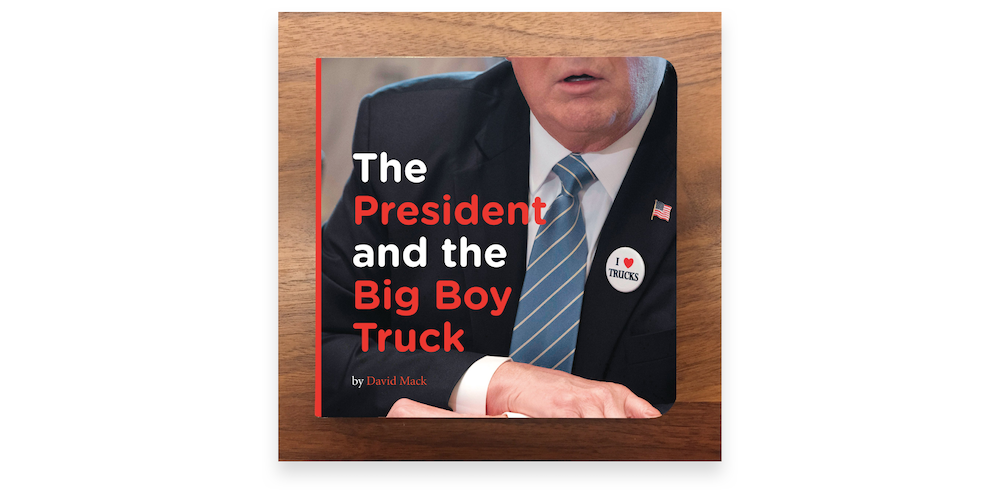

Another case in point: one list that made the rounds on social media was on Donald Trump’s excitement about sitting in Mack trucks. When a reader made the comment, “This article could make a great book,” just like that, it was.

Although the book is no longer available, it illustrates how BuzzFeed is able to take an idea that is creating cultural buzz on the internet and run with it to have, sometimes within hours or days, a product available to sell.

“We love [Shopify] to the moon and back. The speed at which we can allow our talent and community to dream up merch and get it live and attached to content is critical,” Buzzfeed’s former chief commerce officer Ben Kaufman told Shopify in 2018. “Our goal is to create products that are part of and create culture as fast as possible.”

Now, Kaufman is in charge of growth at the BuzzFeed-backed CAMP toy stores—an experimental brand that’s using its publishing platform to drive consumers to its online and brick-and-mortar shops.

Learn more: How Ecommerce Is Revolutionizing the Media and Entertainment Industry

3. The Economist

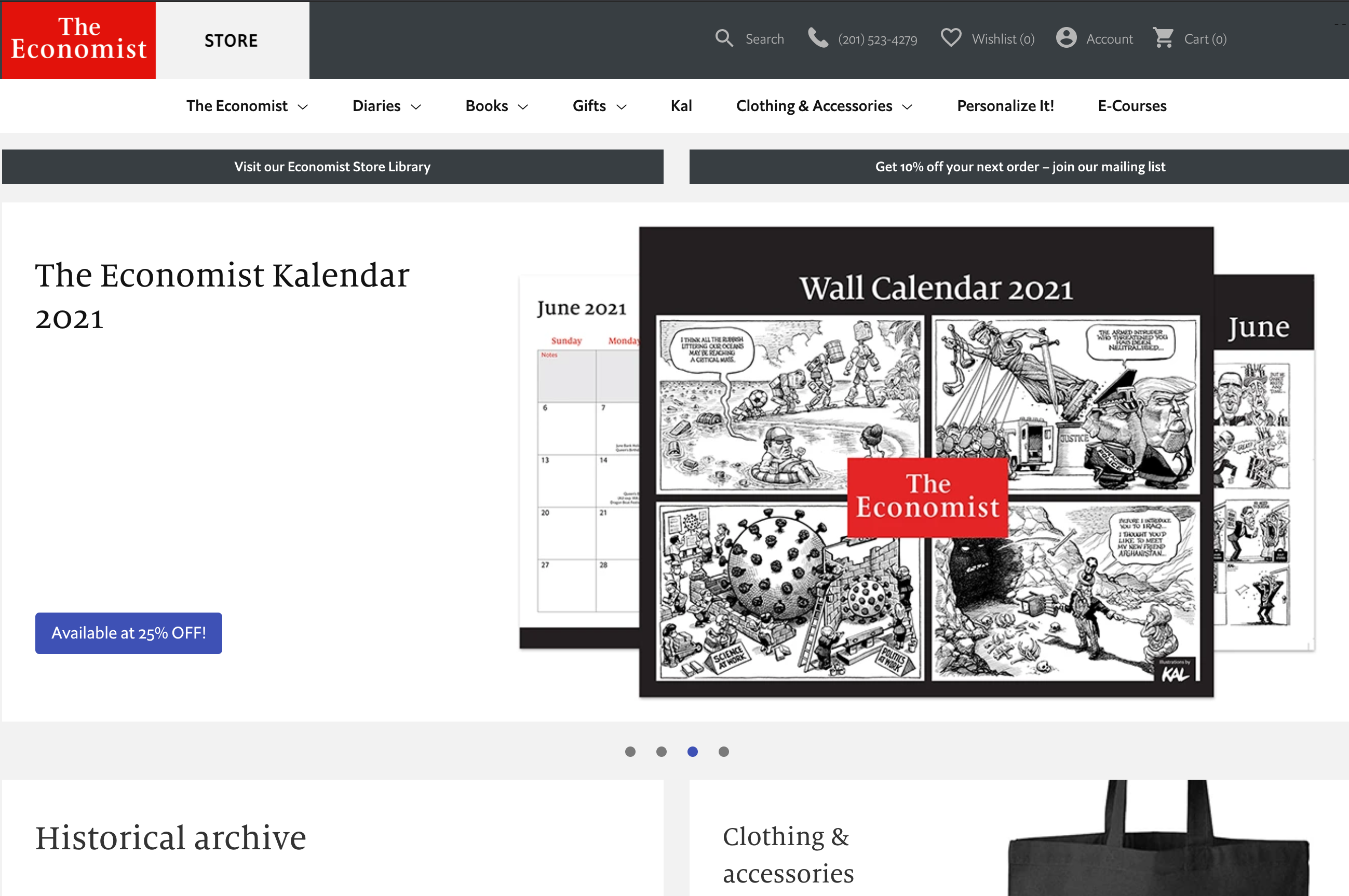

In somewhat similar fashion, The Economist has also joined the ranks of D2C. Its ecommerce store offers not only back issues, diaries, and personalized printing on books, but t-shirts, mugs, and bags—most of which are offered in its trademark red and black.

It also runs a virtual learning center, Learning.ly, where customers can sign up for online courses ranging from science and business to productivity and economics. Books, laminated reference guides, and special reports are also available to purchase through Learning.ly’s ecommerce pillar.

The Economist quickly brought its learning directly to consumers with confidence that Shopify would be able to scale with its growth and expand as it needed to through multiple sales channels.

Learn more: DTC-First: Why More Brands are Using the Direct-to-Consumer Model

4. Condé Nast

Mega-publisher Condé Nast has one of the largest portfolios in the world, not to mention some of the highest profile brands: GQ, Vanity Fair, Vogue, The New Yorker, Wired, and Bon Appétit, amongst others.

That doesn’t mean it’s been immune to declining advertising revenues. To combat this, Roger Lynch—the media group’s chief executive—has laid-out a plan in which readers and ecommerce will be key to Condé Nast’s legacy continuing.

The Financial Times reports that plans are currently underway for exclusive products and services to be launched later in 2021, including a Bon Appétit subscription service, which will allow paying members access to recipes and virtual cooking lessons.

It’s anticipated that by 2024, subscriptions and ecommerce products will make up 30% of the publisher’s revenue.

5. HarperCollins

HarperCollins was in trouble. The ecommerce platform it was using to host Collins Learning—its educational publishing arm—was about to be discontinued. As not to miss a beat, it hired We Make Websites (WMW), an agency that specializes in building in Shopify stores, to help it replatform.

In four months, the agency was able to build a new store that eliminated “nightmare-ish navigation,” helps visitors preview books, lets them pre-order or order, and organizes complex products that often have multiple statuses and formats.

On top of that, WMW also created a much-needed custom checkout for parents and teachers, who are allowed to purchase in slightly different ways:

Only teachers are permitted to purchase a bulk number of textbooks at a lower rate, including evaluation copies—but they must be paid for using a school-registered credit card or school account.

“We really pushed the technical boundaries of Shopify to allow evaluation copies to be purchased and created two strict purchase journeys for the two key markets,” explains WMW’s case study.

6. Penguin UK

Books may not be what comes to mind when you think of “innovation,” but Penguin has always been at the forefront of creative product development and delivery. Its line of affordable quality paperbacks was first conceived of by founder Allen Lane in 1935, when he was waiting for a train without anything to read. Within two years, the first Penguin book vending machine was installed in a train station, and in less than a year, a million books were printed.

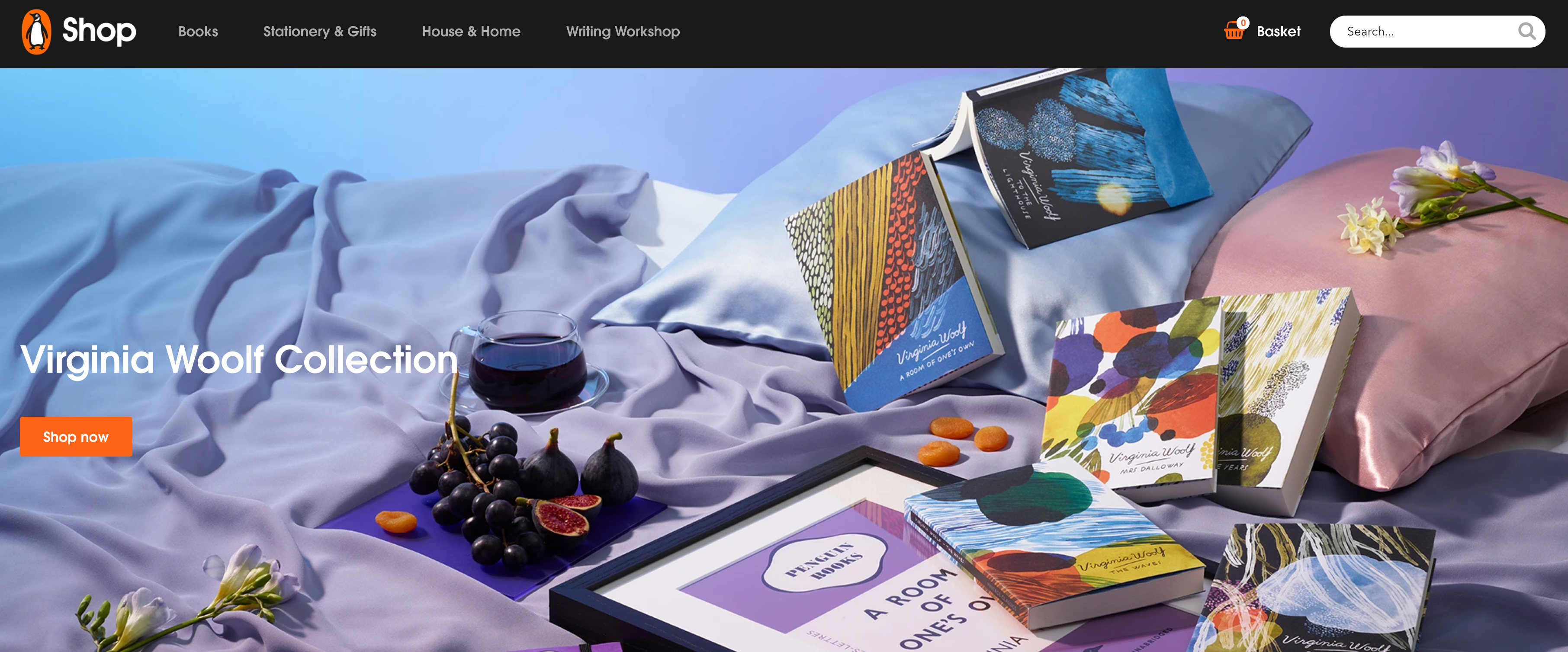

In 2017, the publisher became another client of We Make Websites, when it began selling its iconic colourful paperbacks—alongside tote bags, homewares, and stationary—on the Shopify platform. In the pandemic era, Penguin has also used the store to sell tickets to its exclusive online events, such as writing workshops taught by award-winning authors.

Today, the publisher sells more than 600 million printed books, e-books, and audios books worldwide annually.

7. Los Angeles Times

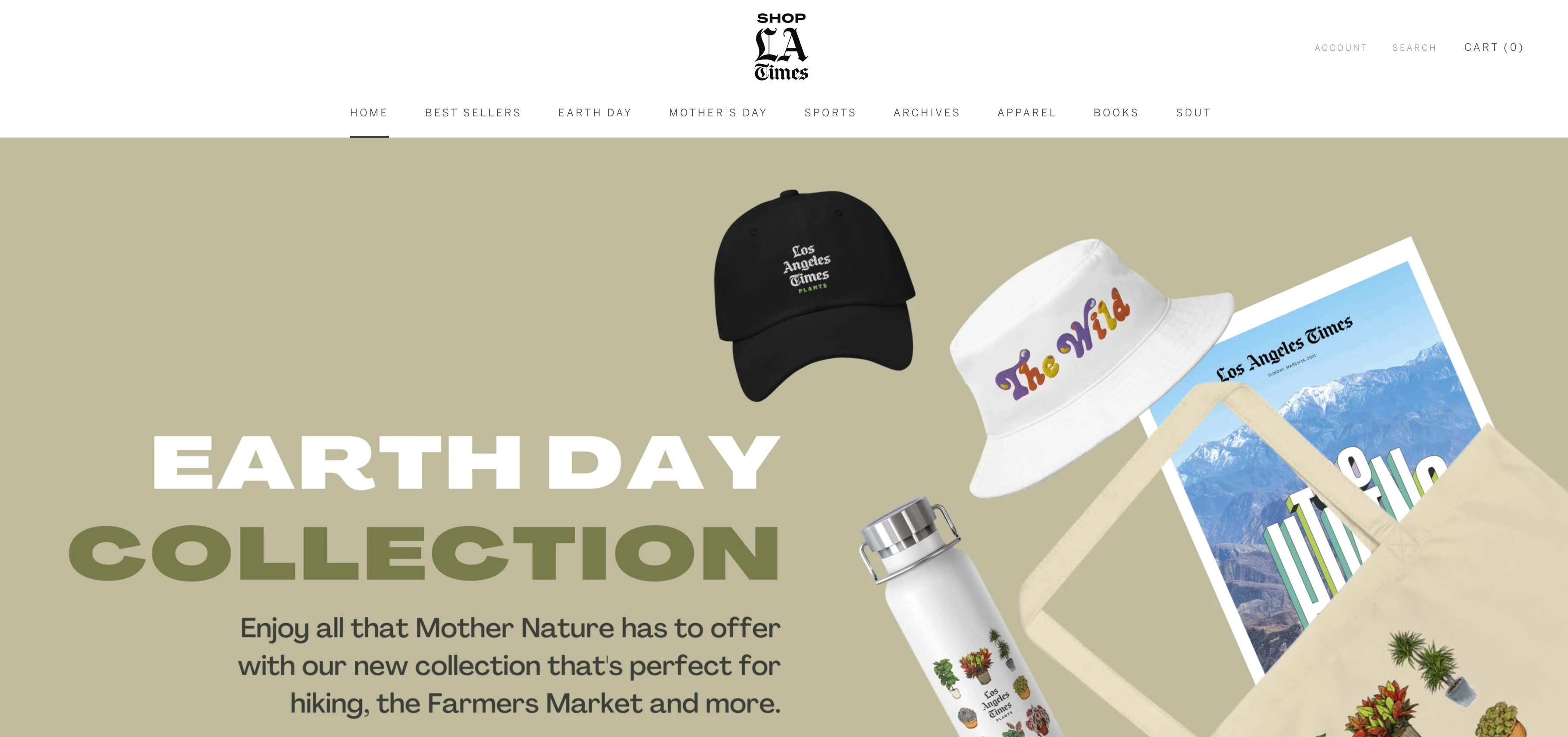

The Los Angeles Times knows its readers—and nothing better reflects this than the products offered through its ecommerce store. Yes, you’ll find everything you’d expect from a newspaper publisher, namely back issues, page prints, and personalized birthday books featuring news clips from chosen dates. But its bestsellers are unique to the residents of the city, including a guide to hiking in LA and a Kobe Bryant memorial magazine, alongside branded apparel.

Rather than risk its store going stagnant, The LA Times also regularly updates products on its site to coincide with holidays such as Earth Day and Mother’s Day—and highlights back issues tied to significant events, such as election issues.

Read more: 3 DTC Brands on How They Build Customer Loyalty

8. Mindbodygreen

In 2017, Mindbodygreen set an ambitious goal. At the time, its eight-figure annual revenue was primarily based on advertising, but it wanted to transition this to 50% from ecommerce.

“Wellness as a category is huge and growing rapidly, and I believe the advertising opportunity alone is as high as $100 million,” said CEO and founder Jason Wachob at the time. “But looking at ecommerce, the opportunity could be even bigger than that.

Mindbodygreen already had a solid revenue stream from selling access to online wellness classes, but the health and wellness publisher was ready to launch its own products. Yet, instead of selling branded yoga mats—a product that would have been easy to launch and well-aligned with its readership—it decided to take a deep dive into the research. What it found was its primary female audience was deeply invested in skincare (they are 5.4 times more likely to have spent $500 or more on skincare in the last six months) and 82% were already taking supplements regularly.

In 2019, Mindbodygreen released its first products: a line of six supplements that focus on improving skin clarity, gut health, and mood support. By 2020, it was well on its way to achieving the goal set out three years earlier, with products projected to reflect nearly a quarter of its revenue.

Publishing and DTC Ecommerce in the 21st Century

As these eight publishers illustrate, publishing is far from dead. By diversifying product offerings and revenue streams via DTC selling, you can deepen the relationship your existing audience has for your outlet.

Read more

- How a Broke Fitness Trainer Accidentally Created a Multimillion-Dollar Business Without Advertising

- How RIPT Apparel Turned $3,000 Into $4 Million Selling One T-Shirt At a Time

- After 10X Holiday Ecommerce Growth, Blenders Eyes More This Black Friday

- How a Seller of Outlandish Party Costumes Optimized Its Warehouse to Grow 400% & Compete With Amazon

- After Ecommerce Sales Surged 72%, Thermacell Turns its Eye to Wholesale

- How Velour Lashes Automates Holiday Ecommerce Sales & Won Beyoncé’s Loyalty

- How A Family Business Left Magento For Shopify Plus & Immediately Doubled Its Conversion Rate While Changing Lives

- How Discount Hockey Lifted Mobile Conversions 26% and Uses Shopify Plus to Sell On & Off the Ice

- How Channelling “Your Inner Ten-Year-Old” Is the Secret to Brandon Steiner’s $50 Million Empire

- How DailySteals.com Used Shopify Plus to Resurrect Itself from the Dead & Generate Millions in Sales

DTC Ecommerce FAQ

What is DTC ecommerce?

DTC (Direct-to-Consumer) ecommerce is a business model in which companies sell their products directly to consumers, bypassing traditional retail channels such as brick-and-mortar stores. This model has become increasingly popular as online shopping has become more prevalent, allowing companies to reach more customers and increase their profits.

Is ecommerce and DTC same?

No, ecommerce and DTC (Direct-to-Consumer) are not the same. Ecommerce is a type of business model that involves buying and selling of goods and services online, while DTC is a type of business model that involves selling directly to consumers without a middleman.

What is the difference between DTC and D2C?

DTC (Direct-to-Consumer) is a retail model where a company sells its products directly to consumers without using a middleman or retailer, typically through an online store. D2C (Direct-to-Consumer) is a business model where a company sells its products directly to consumers through its own online store, bypassing the traditional retail and distribution channels. The main difference between DTC and D2C is the emphasis on the online store. DTC focuses on selling products through an online store, while D2C focuses on building an online store to sell products directly to consumers.